Reviving Silkworms

At HOSOO, we have established HOSOO STUDIES, a research and development department focused on dyeing and weaving, with an aim to link the past with the present and explore the possibilities for the future.

As part of the department’s initiatives, we have been conducting research into ancient plant dyeing. When you hear the words “natural dyes,” you may think of dull colors. Some may think of it as an old technique replaced by chemical dyes once they were developed in a more recent period.

We have been challenging these notions. We have collaborated with outside researchers, questioned our common sense, and conducted the research while extensively reading literature from the past on dyeing and collecting dye materials.

During Nara and Heian periods, natural dyes represented the colors of a royal family and the aristocracy. For example, the color purple, which represented the highest rank toku in the twelve ranks of the noblemen, was produced by a natural dye made from boiled roots of purple gromwell.

Furthermore, as symbolized by the word fukuyo (it means “to take medicine,” but its literal meaning is “to apply clothes”), in ancient times, wearing naturally dyed clothes literally meant taking “medicine.” The Huangdi Neijing (Yellow Emperor’s Inner Classic) — one of the three great classics of Chinese medicine considered to have been complied around 200 B.C. — explains the differences between “small medicine,” “medium medicine,” and “large medicine.” Small medicine meant herb roots and tree bark (today’s herbal medicines), medium medicine meant acupuncture and moxibustion, and large medicine meant food, drink, and clothing. Behind the emphasis on clothes was an idea of taking good elements into one’s body through the skin. The beauty of dyed colors and one’s health used to be the same.

As we went back through the history in our research, we arrived at the conclusion that naturally dyed colors are not at all dull. Natural dyeing can produce exceptionally vivid colors when done at the right timing by a skilled craftsman using carefully selected water and dyes. The resulting colors remain beautiful even though they may change over time. This is why the pieces of cloth kept at the Shosoin Treasure House since the Nara period remain beautiful today.

Aiming to revive such beautiful, ancient natural dyes, we founded the Laboratory of Ancient Dyeing near our Nishijin workshop in 2021. The lab is set up inside an over-100-year-old machiya townhouse that used to be an herbal medicine store. The lab was established in collaboration with Mr. Akira Yamamoto, the only disciple of Mr. Ujo Maeda, a leading researcher of dyeing who was also active as a dyeing artist.

Water is another critical element in dyeing. Nishijin water is known to be soft and suitable for tea, so three Senke schools of tea ceremony have used well water from the same water vein. Nishijin groundwater does not discolor easily as it contains little inclusion, and its temperature remains constant. Therefore, it is considered suitable for dyeing. We follow the ancient method of drawing Nishijin water from a well, putting the water in a wooden bucket, refining, mordanting, and dyeing the yarn. Today’s standard method employs chemical dyes and mordants that help the dyeing process. At the Laboratory of Ancient Dyeing, however, we dye exactly as they did in ancient times without using modern chemical agents. We produce alkaline lye by putting straw ashes (made by burning straw) into Nishijin water and letting it sit for a while. We then refine the yarn using the lye and dye fabrics with natural plant dyes. The resulting colors are astonishingly beautiful.

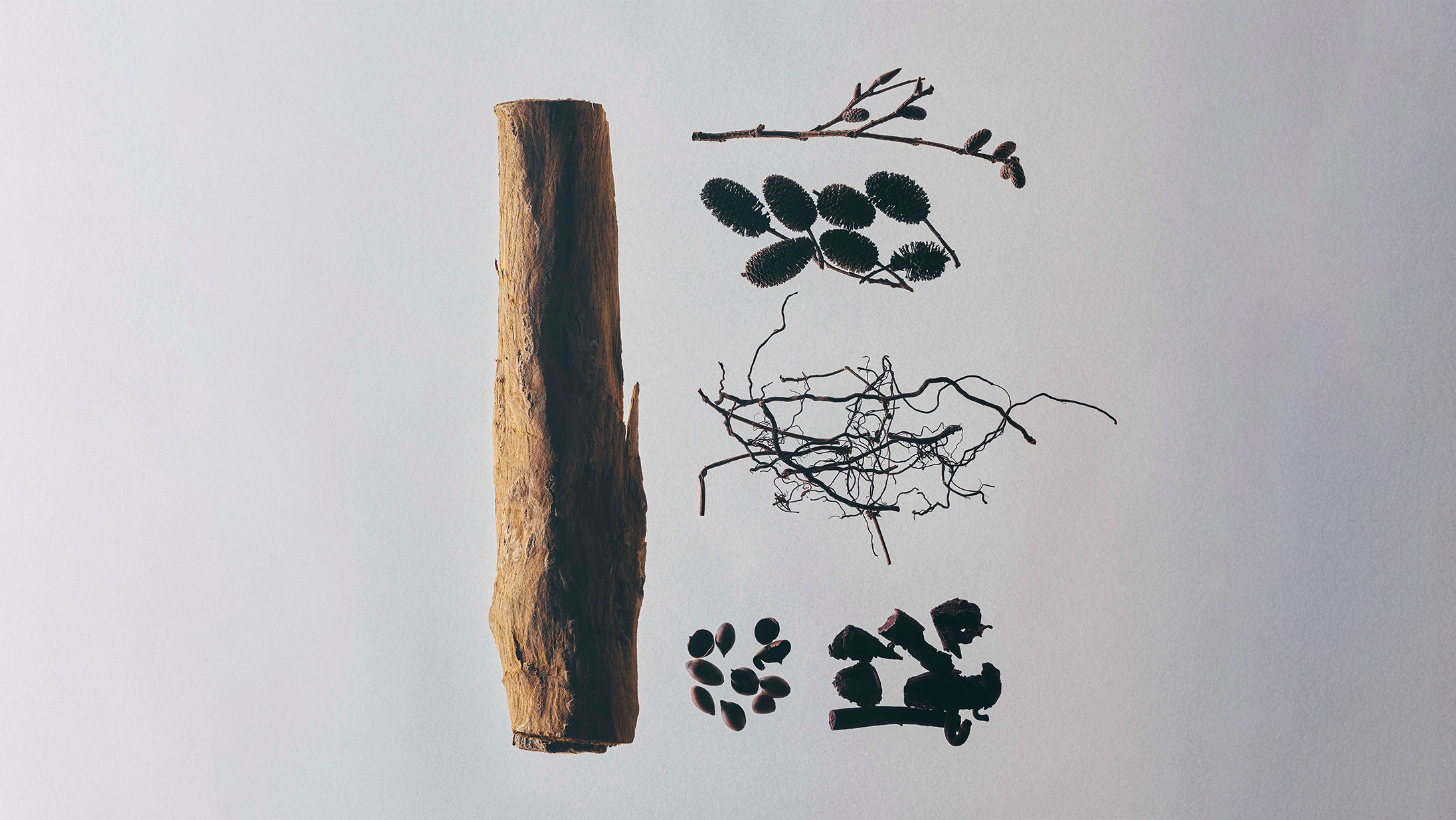

The materials used in plant dyeing are originally living things. If we consider dyeing a process of capturing the lives of such living things, then seasons also become essential. We use seasonal materials at the right timing. With plants, we sometimes use parts other than flowers, such as roots containing seasonal energy, because using flowers does not always bring out colors. Purple gromwell, which produces the purple for the twelve ranks of the noblemen, is now designated as an endangered species but still barely exists thanks to Ise Grand Shrine’s practice of rebuilding its shrine every 20 years. To revive dye plants designated as endangered species, we have prepared a field adjacent to our workshop in Tanba and began their cultivation.

We lost the culture of natural dyeing once. Our mission at the Laboratory of Ancient Dyeing is to revive its lost beauty. Under the guidance of Mr. Yamamoto, we train young craftsmen with the aim of passing the art to the future.